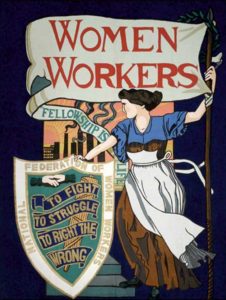

NFWW Banner ©People’s History Museum.

A few employers paid the new rates immediately, but most took refuge in a clause that allowed them to delay increasing pay until 17 August 1910. In the meantime, they resorted to underhand measures. A loophole in the Act allowed workers to contract out of the new rates for a further six months, so the CMA, together with some 30 firms and 150 middlemen outside the association, used the time until August to trick or force the women into signing forms agreeing to contract out of the minimum wage.

Very few of the women could read or write, and everyone found the legal forms confusing. Many signed without understanding what they had done. Those who refused were told that there was no work for them or that the employer could not afford the new rates.

Meanwhile, the employers were stockpiling chains made at the old price. Their plan was to sell these stocks when the new rates became legally binding, make the majority of women unemployed, and render the Trade Boards Act unworkable.

On 23 August, when the women’s union, the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW), drafted another agreement stipulating that the minimum rates should be paid immediately, the employers refused to let the women have new materials and recalled the iron rods which had already been delivered to their workshops.

The union retaliated by calling out on strike those women who were working for less than the minimum rate – and so began the ‘Cradley Heath lockout’, as it was known at the time. (The employers’ action was not a lockout in the true sense since the women were working in their own homes not the employers’ factories and could not therefore be ‘locked out’.)

On 21 August, 400 women attended a meeting at Grainger’s Lane School. Everyone pledged not to sign a form contracting out of the new rate. And so they laid down their hammers.

◄ GLOBAL CONTEXT │ WINNING SUPPORT FOR CRADLEY HEATH’S WOMEN ►