Welcome

In 1910 the women chainmakers of Cradley Heath focussed the world’s attention on the plight of Britain’s lowpaid women workers. In their back yard forges hundreds of women laid down their tools to strike for a living wage.

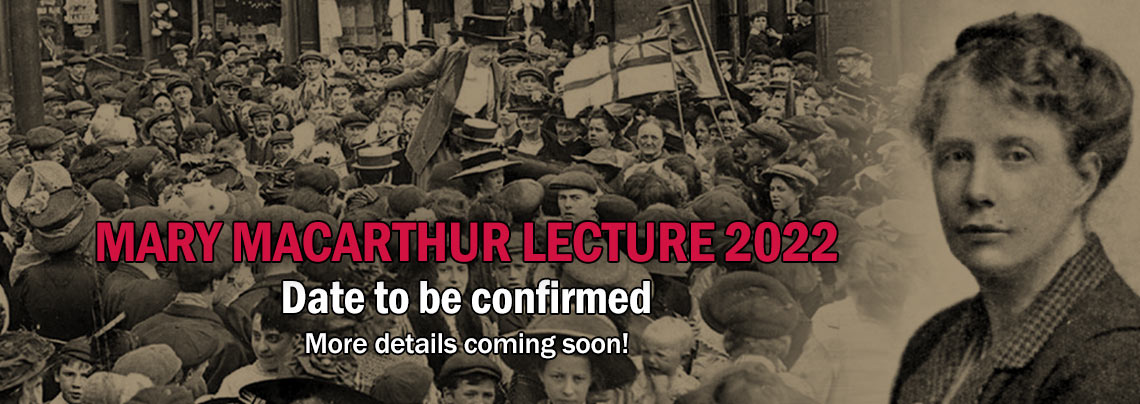

Led by the charismatic union organiser and campaigner, Mary Macarthur, the women’s struggle became a national and international cause célèbre. After ten long weeks, they won the dispute and increased their earnings from as little as 5 shillings (25p) to 11 shillings (55p) a week. Their victory helped to make the principle of a national minimum wage a reality.

Mary Macarthur proposed that surplus money in the strike fund should be used to build a ‘centre of social and industrial activity in the district’. Thousands of local people turned out for the opening of The Cradley Heath Workers’ Institute on 10 June 1912.

The Festival

In 2004, the Workers’ Institute was threatened when plans for a bypass were announced. In 2006, thanks to a Heritage Lottery Fund grant of £1.535 million, the Institute was moved brick by brick to the Black Country Living Museum where it now stands as the last physical reminder of the women’s 1910 strike.

Until the campaign to save the Institute, the story of the Cradley Heath strike was, sadly, largely forgotten, but in 2005 the Museum, in association with the TUC Midlands and many unions, held the first Chainmakers’ Festival. Now an annual event, featuring national entertainers and speakers, including a ‘Mary Macarthur’ in period costume delivering one of Mary’s rousing speeches and a procession of modern unions and ‘strikers’ dressed as Edwardian chainmakers, the festival ensures that this historic episode is celebrated by the local community and trade unionists from all over the country.

Mary Macarthur

Mary Macarthur waged a stunning national campaign, which exposed the chainmasters as perpetuators of sweated labour, and which brought donations flooding in. As well as addressing meetings throughout the land, Macarthur proved an adept ‘spin mistress’, using the media to promote the women’s cause. She offered 79-year-old Patience Round for interview as the oldest woman on the strike, and she had an eye for a good photo as well. Mary would choose the oldest and frailest looking women and would have them drape their chains around their necks, a frequent image which appeared alongside headlines such as ‘Fetters of Fate’ and ‘Women Slaves of the Forge’.

She attracted the whole of the West Midlands’ Conservative press to the side of the women,while the strike was covered by many influential regional dailies in Sunderland, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield, Nottingham, London, Brighton and elsewhere, and she stimulated the interest of major national newspapers.